Command Line and the Unix Shell¶

Setup¶

Launch Atmosphere Instance

- Go to https://atmo.cyverse.org/ and click ‘Projects’ at the top of the page.

- Click the ‘create new project’ button and enter a name and description.

- Click ‘images’ at the top of the screen.

- Select the image called ‘Ubuntu 18.04 GUI XFCE Base’

- Click launch.

- For this work you can leave all the settings as default and click ‘launch instance’.

Once Instance is ‘Active’

- Click on the image name ‘Ubuntu 18.04 GUI XFCE Base’ in your project.

- Click ‘Open Web Desktop’ on the bottom right corner of the screen.

- On web desktop accept ‘default config’.

Get Some Data

- Click the globe icon at the bottom of the Desktop. This will open FireFox.

- Copy this link http://swcarpentry.github.io/shell-novice/data/data-shell.zip to the FireFox search bar to download the data. Choose ‘save file’.

- To move the file to your (web) Desktop open the file manager (folder icon on Desktop). Open the downloads folder. Drag the ‘data-shell.zip’ file onto the Desktop.

- Unzip/extract the file: Right click the file and select ‘extract here’. You should end up with a new folder called ‘data-shell’ on your Desktop.

- Open a terminal by selecting the command line icon at the bottom of the desktop.

- In the terminal, type cd and hit enter.

Background¶

At a high level, computers do four things:

- run programs

- store data

- communicate with each other, and

- interact with us

- The graphical user interface (GUI) is the most widely used way to interact with personal computers.

- give instructions (to run a program, to copy a file, to create a new folder/directory) with mouse

- intuitive and very easy to learn

- scales very poorly

- The shell - a command-line interface (CLI) to make repetitive tasks automatic and fast.

- can take a single instruction and repeat it

Example

If we have to copy the third line of each of a thousand text files stored in thousand different folders/directories and paste it into a single file line by line.

- Using the traditional GUI approach will take several hours to do this.

- Using the shell this will only take a couple of minutes (at most).

The Shell¶

- The Shell is a program which runs other programs rather than doing calculations itself.

- programs can be as complicated as a climate modeling software

- as simple as a program that creates a new folder/directory

- simple programs used to perform stand alone tasks are usually refered to as commands.

- most popular Unix shell is Bash, (the Bourne Again SHell).

- Bash is the default shell on most modern implementations of Unix

To see which shell you are using

$ echo $SHELL

/bin/bash

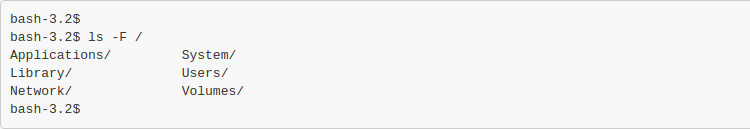

A typical shell window looks something like:

- first line shows only a prompt

- indicates the shell is waiting for input

- your shell may use different text for the prompt

- do not type the prompt, only the commands that follow it

- the second line

- command is ls, with an option -F and an argument /

- options change the behavior of a command

- each part is separated by spaces

- capitalization matters

- commands can have more than one option or arugment

- commands don’t always require and option or argument

- lines 3-5 contain output that command produced

- this is a list of files and folders in the root directory (/)

Finally, the shell again prints the prompt and waits for you to type the next command.

Warning

Spaces and capitalization are important!

The command line is always case sensitive.

There is always a space between command and option.

Hint

To re-enter the same command again use the up arrow to display the previous command. Press the up arrow twice to show the command before that (and so on).

Working with Files and Directories¶

Creating directories (mkdir)¶

As you might guess from its name, mkdir means “make directory”. Make a new directory called thesis.

$ mkdir thesis

Since thesis is a relative path (i.e., does not have a leading slash, like /what/ever/thesis), the new directory is created in the current working directory:

$ ls -F

creatures/ data/ molecules/ north-pacific-gyre/ notes.txt pizza.cfg

solar.pdf thesis/ writing/

Good Names for Files and Directories

Complicated names of files and directories can make your life painful when working on the command line. Here we provide a few useful tips for the names of your files.

Don’t use spaces.

Spaces can make a name more meaningful, but since spaces are used to separate arguments on the command line it is better to avoid them in names of files and directories. You can use - or _ instead (e.g. north-pacific-gyre/ rather than north pacific gyre/).

Don’t begin the name with - (dash).

Commands treat names starting with - as options.

Stick with letters, numbers, . (period or ‘full stop’), - (dash) and _ (underscore).

If you need to refer to names of files or directories that have spaces or other special characters, you should surround the name in quotes (“”).

Since we’ve just created the thesis directory, there’s nothing in it yet:

$ ls -F thesis

Creating a text files¶

With a text editor¶

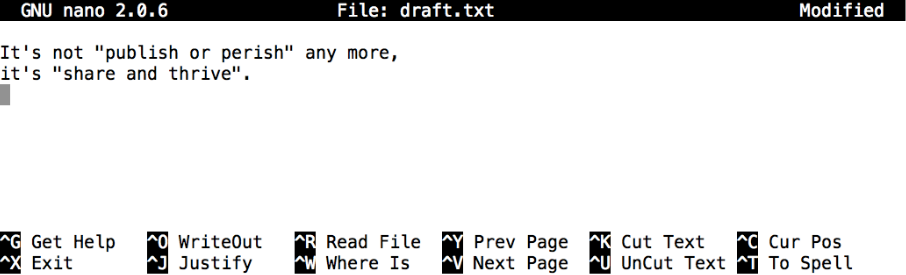

Let’s change our working directory to thesis using cd, then run a text editor called Nano to create a file called draft.txt:

$ cd thesis

$ nano draft.txt

Let’s type in a few lines of text. Once we’re happy with our text, we can press Ctrl+O (press the Ctrl or Control key and, while holding it down, press the O key) to write our data to disk (we’ll be asked what file we want to save this to: press Return to accept the suggested default of draft.txt).

Once our file is saved, we can use Ctrl-X to quit the editor and return to the shell.

In nano, along the bottom of the screen you’ll see ^G Get Help ^O WriteOut. This means that you can use Control-G to get help and Control-O to save your file.

nano doesn’t leave any output on the screen after it exits, but ls now shows that we have created a file called draft.txt:

$ ls

draft.txt

With touch¶

We have seen how to create text files using the nano editor. Now, try the following command:

$ touch my_file.txt

What did the touch command do?

Use ls -l to inspect the files. How large is my_file.txt?

$ ls -l

Note

You may have noticed that files are named “something dot something”, and in this part of the lesson, we always used the extension .txt. This is just a convention: we can call a file mythesis or almost anything else we want. However, most people use two-part names most of the time to help them (and their programs) tell different kinds of files apart. The second part of such a name is called the filename extension, and indicates what type of data the file holds.

Naming a PNG image of a whale as whale.mp3 doesn’t somehow magically turn it into a recording of whalesong, though it might cause the operating system to try to open it with a music player when someone double-clicks it.

Moving files and directories (mv)¶

Returning to the data-shell directory,

$ cd ~/Desktop/data-shell/

In our thesis directory we have a file draft.txt which isn’t a particularly informative name, so let’s change the file’s name using mv, which is short for “move”:

$ mv thesis/draft.txt thesis/quotes.txt

The first argument tells mv what we’re “moving”, while the second is where it’s to go. In this case, we’re moving thesis/draft.txt to thesis/quotes.txt, which has the same effect as renaming the file. Sure enough, ls shows us that thesis now contains one file called quotes.txt:

$ ls thesis

quotes.txt

Warning

One has to be careful when specifying the target file name, since mv will silently overwrite any existing file with the same name, which could lead to data loss. An additional option, mv -i (or mv –interactive), can be used to make mv ask you for confirmation before overwriting.

mv also works on directories

Let’s move quotes.txt into the current working directory. We use mv once again, but this time we’ll just use the name of a directory as the second argument to tell mv that we want to keep the filename, but put the file somewhere new. (This is why the command is called “move”.) In this case, the directory name we use is the special directory name ‘.’ that we mentioned earlier.

$ mv thesis/quotes.txt .

The effect is to move the file from the directory it was in to the current working directory. ls now shows us that thesis is empty:

$ ls thesis

Copying Files and Directories (cp)¶

The cp command works very much like mv, except it copies a file instead of moving it. We can check that it did the right thing using ls with two paths as arguments — like most Unix commands, ls can be given multiple paths at once:

$ cp quotes.txt thesis/quotations.txt

$ ls quotes.txt thesis/quotations.txt

quotes.txt thesis/quotations.txt

We can also copy a directory and all its contents by using the recursive option -r, e.g. to back up a directory:

$ cp -r thesis thesis_backup

We can check the result by listing the contents of both the thesis and thesis_backup directory:

$ ls thesis thesis_backup

thesis:

quotations.txt

thesis_backup:

quotations.txt

Removing files and directories (rm)¶

Returning to the data-shell directory, let’s tidy up this directory by removing the quotes.txt file we created. The Unix command we’ll use for this is rm (short for ‘remove’):

$ rm quotes.txt

We can confirm the file has gone using ls:

$ ls quotes.txt

ls: cannot access 'quotes.txt': No such file or directory

rm can remove a directory and all its contents if we use the recursive option -r, and it will do so without any confirmation prompts:

$ rm -r thesis

Warning

Deleting Is Forever

The Unix shell doesn’t have a trash bin that we can recover deleted files from. Instead, when we delete files, they are unlinked from the file system so that their storage space on disk can be recycled. Given that there is no way to retrieve files deleted using the shell, rm -r should be used with great caution (you might consider adding the interactive option rm -r -i).

Operations with multiple files and directories¶

Oftentimes one needs to copy or move several files at once. This can be done by providing a list of individual filenames, or specifying a naming pattern using wildcards.

Copy with Multiple Filenames

For this exercise, you can test the commands in the data-shell/data directory.

In the example below, what does cp do when given several filenames and a directory name?

$ mkdir backup

$ cp amino-acids.txt animals.txt backup/

If given more than one file name followed by a directory name (i.e. the destination directory must be the last argument), cp copies the files to the named directory.

Using wildcards for accessing multiple files at once

* is a wildcard, which matches zero or more characters. Let’s consider the data-shell/molecules directory: *.pdb matches ethane.pdb, propane.pdb, and every file that ends with ‘.pdb’. On the other hand, p*.pdb only matches pentane.pdb and propane.pdb, because the ‘p’ at the front only matches filenames that begin with the letter ‘p’.

? is also a wildcard, but it matches exactly one character. So ?ethane.pdb would match methane.pdb whereas *ethane.pdb matches both ethane.pdb, and methane.pdb.

Wildcards can be used in combination with each other e.g. ???ane.pdb matches three characters followed by ane.pdb, giving cubane.pdb ethane.pdb octane.pdb.

Other Useful Tools and Commands¶

sudo¶

allows users to run programs with the security privileges of the superuser

This command is used as a prefix to other commands that you need elevated permissions to run. Which commands you will need this for will vary depending on the computer you are using at the time. If you receive a permission denied error it is likely that you will need ‘sudo’ to run the command.

$ docker run hello-world:latest

$ sudo docker run hello-world:latest

Note

Use ‘sudo’ with caution. Sometimes important files restrict permission because they are very senstive and it is un-wise to change them unless you know what you are doing.

head¶

prints the first few (10 by default) lines of a file

$ head data/sunspot.txt

(* Sunspot data collected by Robin McQuinn from *)

(* http://sidc.oma.be/html/sunspot.html *)

(* Month: 1749 01 *) 58

(* Month: 1749 02 *) 63

(* Month: 1749 03 *) 70

(* Month: 1749 04 *) 56

(* Month: 1749 05 *) 85

(* Month: 1749 06 *) 84

(* Month: 1749 07 *) 95

tail¶

prints the last few (10 by default) lines of a file

$ tail data/sunspot.txt

(* Month: 2004 05 *) 42

(* Month: 2004 06 *) 43

(* Month: 2004 07 *) 51

(* Month: 2004 08 *) 41

(* Month: 2004 09 *) 28

(* Month: 2004 10 *) 48

(* Month: 2004 11 *) 44

(* Month: 2004 12 *) 18

(* Month: 2005 01 *) 31

(* Month: 2005 02 *) 29

history¶

displays the last few hundred commands that have been executed

$ history

1988 cd ..

1989 ls

1990 cd data-shell/

1991 ls

1992 mkdir thesis

1993 ls

1994 ls-F

1995 ls

1996 cd Desktop/data-shell/data/

1997 pwd

1998 cd ..

1999 pwd

2000 ls -F

2001 cd Desktop/data-shell/

2002 head data/sunspot.txt

2003 tail data/sunspot.txt

2004 history

grep¶

finds and prints lines in files that match a pattern

$ cd

$ cd Desktop/data-shell/writing

$ cat haiku.txt

The Tao that is seen

Is not the true Tao, until

You bring fresh toner.

With searching comes loss

and the presence of absence:

"My Thesis" not found.

Yesterday it worked

Today it is not working

Software is like that.

$ grep "not" haiku.txt

Is not the true Tao, until

"My Thesis" not found

Today it is not working

find¶

finds files

To find all the files in the ‘writing’ directory and sub-directories

$ find .

.

./thesis

./thesis/empty-draft.md

./tools

./tools/format

./tools/old

./tools/old/oldtool

./tools/stats

./haiku.txt

./data

./data/two.txt

./data/one.txt

./data/LittleWomen.txt

To find all the files that end with ‘.txt’

$find -name *.txt

./haiku.txt

echo¶

print stings (text)

This is especially useful when writing Bash scripts

$echo hello world

hello world

>¶

prints output to a file rather than the shell

$ grep not haiku.txt > not_haiku.txt

$ ls

data haiku.txt not_haiku.txt thesis tools

|¶

directs output from the first command into the second command (and the second into the third)

$ cd ../north-pacific-gyre/2012-07-03

$ wc -l *.txt | sort -n | head -n 5

240 NENE02018B.txt

300 NENE01729A.txt

300 NENE01729B.txt

300 NENE01736A.txt

300 NENE01751A.txt

wget

downloads things from the internet

$ cd ~/Desktop

$ rm data-shell.zip

$ wget http://swcarpentry.github.io/shell-novice/data/data-shell.zip

Getting help and further learning¶

Note

This is was just a brief summary of how to use the command line. There is much, much more you can do. For more information check out the Software Caprentry page.

There are two common ways to find out how to use a command and what options it accepts:

The help option

We can pass a –help option to the command, such as:

$ ls --help

The man command

The other way to learn about ls is to type

$ man ls

This will open the manual in your terminal with a description of the ls command and its options and, if you’re lucky, some examples of how to use it.

To navigate through the man pages, you may use ↑ and ↓ to move line-by-line, or try B and Spacebar to skip up and down by a full page.

To quit the man pages, press q.

Manual pages on the web

Of course there is a third way to access help for commands: searching the internet via your web browser. When using internet search, including the phrase unix man page in your search query will help to find relevant results.GNU provides links to its manuals including the core GNU utilities , which covers many commands introduced within this lesson.

- On Github: |Github Repo Link|

- Send feedback: Tutorials@CyVerse.org